In order to write well, these 3 things are important:

- The letters have some sort of meaning, purpose, and are not just unintelligible marks to the child

- The letters are formed correctly from the start, so there is no bad habit to break and writing is efficient and more easily legible (poor habits lead to illegibility later, when writing speeds up)

- There is adequate strength and security in grasping the writing utensil, so that the hand and fingers can relax and make small controlled movements

Reading: The Purpose of Letters

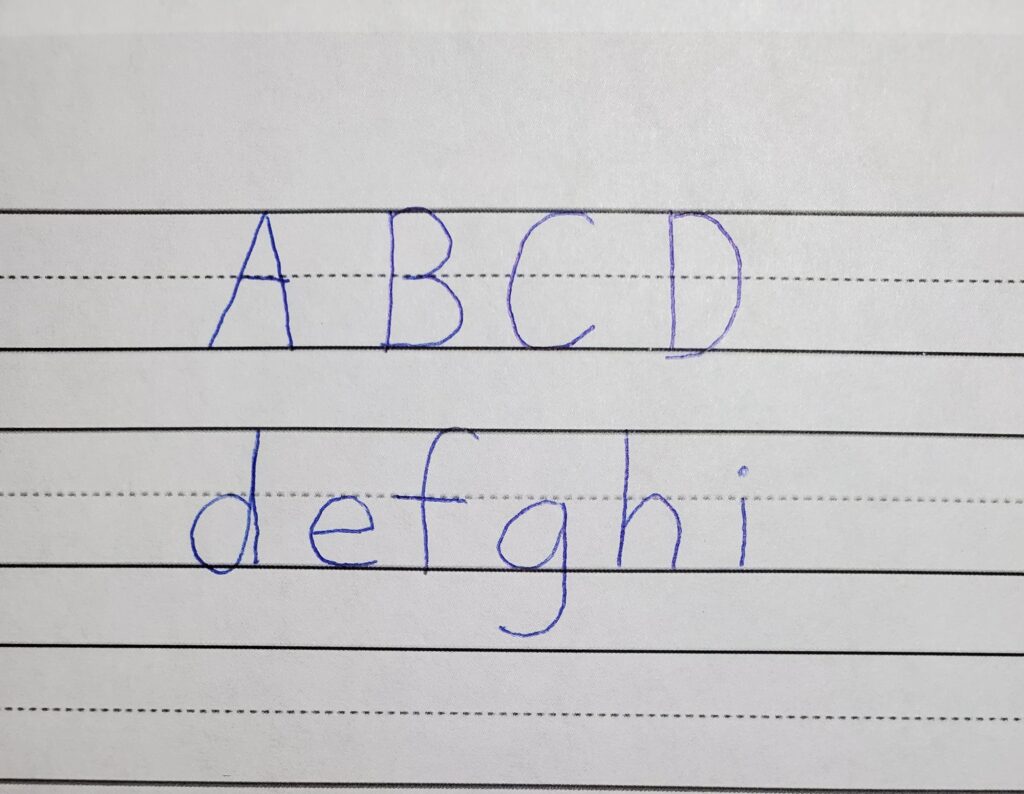

As has been demonstrated through Montessori techniques, children can, and often do, learn to read before having the fine- and visual-motor control for writing; indeed, many learn at age 3 or 4 how to read, while control for handwriting generally does not emerge until closer to ages 5-7. Reading at a younger age is done by removing unnecessary steps to reading. For example, it is more necessary to know the sounds letters make than to know what the name of a letter is, so skipping the naming and going straight to the sounds has benefits: instead of saying “ay” when pointing to “A” or “a”, say the short sound a (as in “cat”). Additionally, since most words in most books are written entirely in lowercase letters, teaching lowercase letters first helps jump start reading. That way, when the child learns the sounds to the lowercase letters c-a-t, the connection of letter sound to actual word is more direct, and what would be read in a book. The messier alternative is something like (name) “C-A-T spells ‘cat’ because C makes the ‘k’ sound, A makes the “a” sound, and T makes the ‘t’ sound — and by the way, ‘a’ and ‘t’ look different because they’re lowercase, which you’ll learn later!”

Writing: Making it Meaningful

It is very true that when writing, uppercase letters are easier to learn first, because they are all the same height and sit on the baseline without ever going below the baseline or stopping halfway up (at the dotted middle line in triple-lined paper). Yet it is somewhat of a logical fallacy to think we should teach uppercase letters first because that is what kids can write first — teach what they can read first, and make sure it is immediately applicable (books are not written all uppercase). When we teach kids the symbols for sounds used to form words (letters) that they can read quickly and efficiently, each letter has meaning and purpose, and is “understood”, rather than teaching how to write letters before reading, which is like teaching meaningless designs.

Letter Formation:

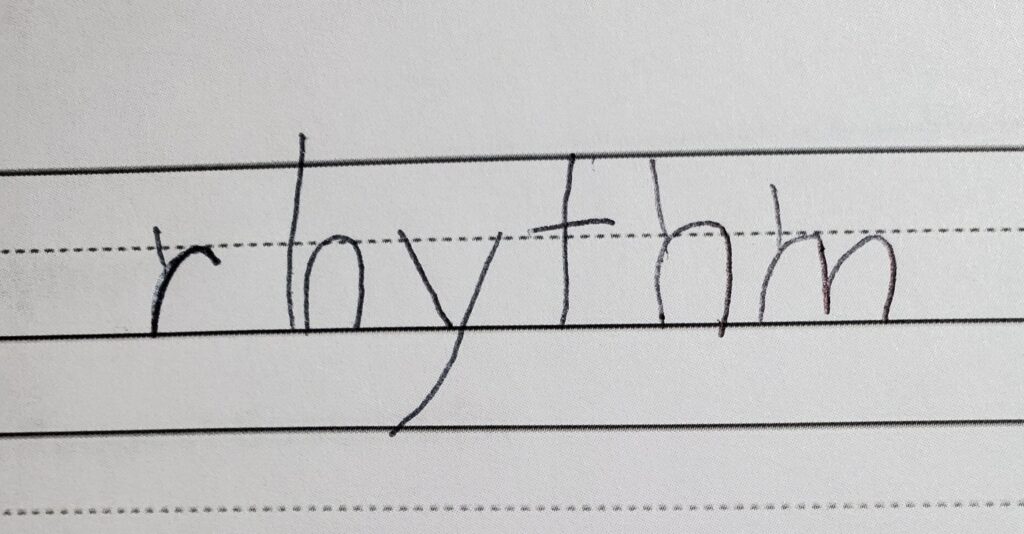

It is important to teach that most strokes move left to right and top to bottom. Imagine crossing a series of “t”s moving to the right for each successive “t” but crossing each from right to left (not efficient). Many kids in therapy have low tone, with a tendency to make lines from the bottom moving up. I think this is akin to resting one’s hand, holding a pencil, on a table with the relaxation pushing the pencil tip upward. With better strength and tone, the pencil is pulled toward the hand to make a down stroke.

Being too complex: When kids are not taught correct letter formation and have a tendency to write “bottom up”, we see letters being made with too many steps, like making the humps of r,n,m,h, then going back to add the straight line or stem. Once writing faster, this results in lines disconnected from humps or appearing like stems in the middle of humps, with much more room for error and much greater need for attention to handwriting and stroke placement when ideally the child is focusing more on content than the mechanics of writing (this is also an argument for cursive writing for some children, removing the need to lift and replace the pencil precisely for every single letter).

Being over-simple: Alternately, some letters are drawn too simply, like sweeping a “b” down and around counterclockwise (or worse, sweeping from the bottom into a clockwise loop, then straight up) causing it to easily be mistaken for the number 6.

Strength and Control for Handwriting:

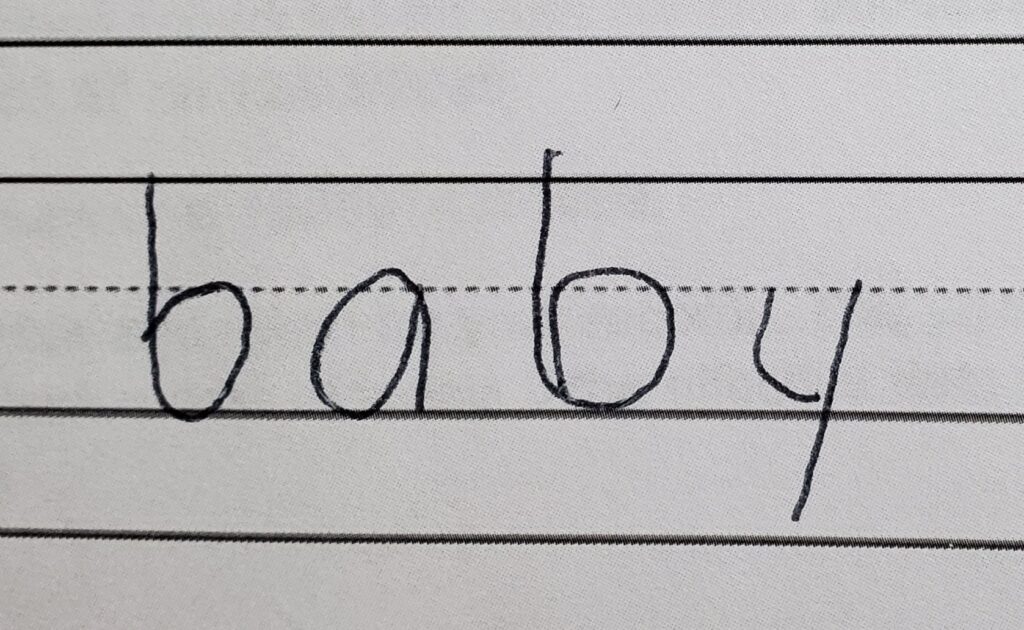

Many kids I work with have a hard time sensing how much strength or force they are using as well as sensing how firmly or loosely something is held. In other words, they may grasp a pencil very loosely and end up with poor control of the pencil for writing, or they may fear the pencil may fall out of their hand and use a variety of strong or bracing grasps to ensure this doesn’t happen, but sacrificing the ability to make small controlled movements in the fingers. There are two main ways to assist this: 1) improve strength and awareness in the fingers, which can be done with a variety of activities other than writing, and 2) use pencil grips that help one’s grasp feel secure, so the hand can relax and finger dexterity has a chance to emerge.

Best tools & Strategies

I often work on one skill at a time, particularly when working with kids with sensory challenges. For example, if grasp and control of a writing utensil is extremely difficult, I do not want to put other skills on hold, such as learning correct letter formation or understanding letter-sound associations, while we work on controlling a writing utensil. Therefore, I remove the need to grasp and control a writing utensil when working on letter formation, and I remove the need to form letters when working on grasp and control of a writing utensil. These skills can blend together after there is some proficiency with each on its own. For letter formation, I like to use apps, which inherently only require controlling position in space of an index finger, and when using a good app, prevent learning poor habits with letter formation.

The app “Touch and Write” (an Apple product) teaches correct letter formation (many tracing apps don’t) by having the child move a monster to eat cupcakes in the right order to trace each letter. When the child is more familiar with each formation, the cupcakes can be disabled and the child is “tested” on where to start and which direction to move. The app also has a phonics mode so that after a letter is traced, the sound (rather than the letter name) is heard, reinforcing letter-sound associations. The app comes with word lists, so one can hear how each letter traced comes together to form a word. There is also an option to create one’s own word list, which can be very helpful for a child learning to write their own name, or practicing sight words or spelling words for school.

“Writing Wizard” by L’Escapadou has a step more basic. It has a design section that is very helpful for kids who do not yet have the visual motor control to keep their index fingers on the lines yet. Typical progression for skill development is to copy or trace vertical lines (top to bottom), then horizontal lines, then circles, crosses, and diagonals (the latter three can be particularly challenging). Once a design is traced there is a motivating visual treat at the end that changes each time (rotating through several different ones); for example, the entire traced design may be dragged off the model and moved around for fun, or the traced marks may conglomerate around the finger to be dragged wherever the finger goes, or the design may “fall off” and become like water than can be tilted to slosh around the screen. Therefore, if a child needs to work on cause and effect, needs high visual stim to engage, or motivation to even begin the process of tracing, this app helps: a parent can trace at first so the child can engage with the “reward” and eventually try the tracing themselves, practicing using their own index finger or grasping and guiding the adult index finger almost like a writing utensil (but the adult can ensure there will be success). Alternately, there is a cursive version of this app that can be useful for kids wanting to learn cursive letter formation.

A step even more basic than this can be found in a valuable collection of early childhood apps called “Injini” which has kids moving their index finger across sheep to shear them, or across pigs to wash them (essentially learning to color and not miss areas). And if the child has trouble sensing their own fingers and fingertips and position in space, such sensation can be reinforced by engaging in repeated tapping with the index finger, like targeting and tapping eggs three times to break the shell to watch a chick or duckling emerge. Other activities in the collection work on matching skills, puzzle skills, sequencing skills, learning colors, targeting moving objects, and more.

Assisting Grasp:

Pencil grips are for fostering trust in a secure grasp so the focus changes from just holding a utensil powerfully/securely to being able to relax and control the utensil using the smaller muscles of the fingers in a more coordinated way. I like the “Grotto Grip” because the hood over the index and middle fingers makes it feel like even if the fingers are lifted (or not pushing down enough), the pencil won’t drop. Not adequately feeling the grasp, or feeling like the pencil may drop, is the biggest contributor to hands tensing up and braced or power grasps (maladaptive) being used.

Some kids have a hard time with curling the ring and pinky fingers under while using the thumb, index and middle fingers to write (all fingers may end up extended, with the child trying to pinch the pencil between the thumb and side of hand. This is an issue of the two main nerves to the hand (radial and ulnar) not acting differentiated enough. Helping a child do one thing with one side of the hand (hold a pencil) while doing another thing with the other side of the hand (curl fingers out of the way) is assisted with grips like this.

The Firesara pencil grips, monkey-style, have tails that extend toward the palm encourage the child to curl/close the ring and little finger to hold the tail while writing (without the finger “hood”). The puppy version also includes the hood over the fingers to support security. Once the ideal position for writing is attained the child can be weaned from these pencil grips if desired.

Rules of “Thumb”

Writing utensils should typically always be held with the thumb and index finger toward the writing tip. Typical toddlers will naturally grasp writing utensils palm down with the tip nearest the thumb (pointing toward midline), tilting the hand thumb-toward-paper (or egg, in this case) to scribble, and this is good. As muscles and coordination develop, grasp moves toward the fingertips and the back of the pencil eventually flips from under the palm to emerging over the thumb webspace. When a child grasps a pencil in a “power grasp” (the position you use to grasp a cup) with the tip pointing down (on the pinky side of the hand), this is a warning sign of low tone or strength, or low proprioception (sensation and sense of control) — even though you may have seen this poor hand position with children in advertisements! This position provides a sense of strength and secure grasp, but with no ability to finely control movements, because the tip of the writing utensil is on the power side of the hand rather than the control side; it suggests that the child has some underlying weakness or poor sensation, and may need some guidance to assist healthy development of coordination for utensil use.